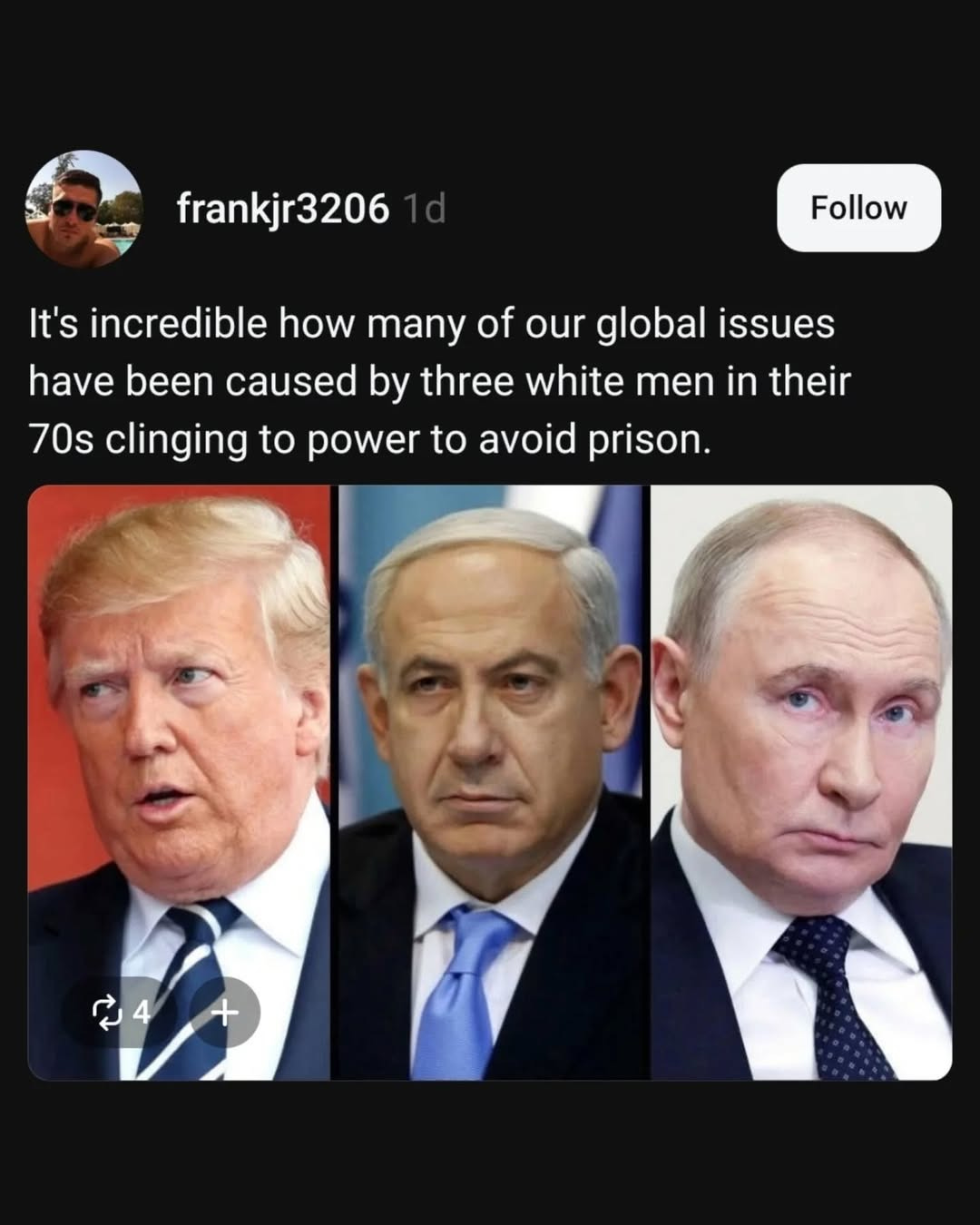

Matters of Recognition Pt.2

“The sum of western guilt sat next to him on the couch and went to bed with him at night.” – Omniscient Narrator

“The sum of western guilt sat next to him on the couch and went to bed with him at night.” – Omniscient Narrator

Here weeeee areeeeee! This is Goodness Osih bringing you Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Pt.2. Kidding. I know I’m not beating the absentee-writer allegations. However, before you say anything, at least I beat Warner Bros. in the time it took me to release a sequel. Early in September, I woke-up to birthday messages and my fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders (i.e. Pooja & Alexis & Amanda) requiring that I finish this post. Confidently, I will maintain that four months to deliver “Pt.2” should be counted in the “brief hiatus” camp, though, at this time, I will forgo checking the legal definition. My closing argument: it is but a few weeks shy of a Selena Gomez social media break.1

Look, if you’re still upset – I get it. I demanded a rebrand, then promptly disappeared without providing any direction. Classic male behaviour, amirite? Well, I was stumped! Harboring a mere sprinkle of a fragment of an inkling of an idea on how to save Masculinity: The Brand. In such troubling cases one could use the help of a classic male sociologist. So I’ve donned my Simon Sinek thinking cap, tilted it to the side, and instead of “Start with Why”, suggest we start with the core of the brand. What is masculinity? It is the strict set of rules about how boys should be; the noose tied around boys’ necks with a knot named “How to Be A Man”. If we were to make an incision, hoping to refashion that tie into, say, a butterfly, we must then ask the question… when does a boy even become one?

I don’t think it works like Grease. Where once you buy a leather jacket, or drive a car, or fuck a girl at the skeevy lookout spot, you’re in the gang. Apologies for being so rough with the language on that last one – like really, the hard f ? – but the pedagogy is haphazard for male status symbols. A softer approach: does a boy become a man when he graduates from the omnipresent navy-blue Walmart sheets to a respectable colour? Perhaps olive-green, emulating the image of perfect sleep, sprawling over his 8 x 11 foot kingdom; a king cozied up in his queen. It’s no more winning your first fight than it is going off to your first war. Though my gut says the latter is closer.

That’s unfair, isn’t it? Asking you for Time without establishing Speed. Here’s a hand: assume every boy leads at his own pace. Transitions from boy to man at a rate comfortable with the expectations lauded, baked into them from the moment their gooey smile landed in a blue crib. Now we’re only missing one, Distance, before we’re able to reverse-engineer Time from all three. But we can’t reach Distance without a destination. Leading us to another question: “when does a boy become a man...” well, what exactly is said boy getting themselves into?

When we tell you to “Be a Man”, we say it with the impression that a Man is an ideal. That word, ideal, evokes a spirit of shed selfishness; stalwartness; good extending out to others; service. It twists our mission to save masculinity on its uncertain faults and into a riddle. If a “Man” is an ideal, then a boy becomes one not through one singular action, but a series of actions. Manhood, then, is not reached at an age but through a culmination of instances. A tipping point in the frequency with which one’s character displays certain qualities. And the body that houses said spirit? How well a boy enacts their will. How capable he is at doing what he sets out to do. “Be a Man” becomes “Be Progenitors & Executors of Your Ambition.” In doing this, and to cheat the Catholics out of a good saying, “Manliness becomes next to godliness”. The upside being we persuade boys to pay checks and act with integrity, yoking them to accountability and a sense of care for others. In flickers, we market “Man” as a force for good.2

But there are downsides, too. Perched and prideful, masculinity strips its men of their humanity, because gods do not fail.3 Gods do not cry. Gods do not grow weary or weak. Gods make no mistakes, so they issue no apologies. They are not to be disagreed with by their worshippers and if met with either doubt or resistance, their sole recourse is to rain4 down fury. So if you are going to be a Man, and by proxy a god, you must uphold all these impossibilities.

Ain’t that some shit - when arguably us dudes ain’t even all that! What a played-out paradox! What a rotten-to-the-core brand promise. During my hiatus, I found that John Fowles, in a passage laying out the debilitating effects of Victorian hypocrisy, somehow managed to sum up the crux of our machismo problem:

“What are we faced with in the nineteenth century? An age where woman was sacred; and where you could buy a thirteen-year-old girl for a few pounds—a few shillings, if you wanted her for only an hour or two. Where more churches were built than in the whole previous history of the country; and where one in sixty houses in London was a brothel (the modern ratio would be nearer one in six thousand). Where the sanctity of marriage (and chastity before marriage) was proclaimed from every pulpit, in every newspaper editorial and public utterance; and where never—or hardly ever— have so many great public figures, from the future king down, led scandalous private lives. Where the penal system was progressively humanized; and flagellation so rife that a Frenchman set out quite seriously to prove that the Marquis de Sade must have had English ancestry. Where the female body had never been so hidden from view; and where every sculptor was judged by his ability to carve naked women. Where there is not a single novel, play or poem of literary distinction that ever goes beyond the sensuality of a kiss, where Dr Bowdler (the date of whose death, 1825, reminds us that the Victorian ethos was in being long before the strict threshold of the age) was widely considered a public benefactor; and where the output of pornography has never been exceeded. Where the excretory functions were never referred to; and where the sanitation remained —the flushing lavatory came late in the age and remained a luxury well up to 1900—so primitive that there can have been few houses, and few streets, where one was not constantly reminded of them. Where it was universally maintained that women do not have orgasms; and yet every prostitute was taught to simulate them. Where there was an enormous progress and liberation in every other field of human activity; and nothing but tyranny in the most personal and fundamental.” [The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Chapter 35, pg. 261]

Sadness and rage do somersaults inside me. I’ve got a touch of the Dementor swirling around.

What am I to be?

It’s unclear who I want to be for this next year. Maybe, also, entirely, for this next phase of life. The future feels fuzzy and dark, and for once, I am chagrined by Virginia Woolf’s take on it.5 Hopeful acceptance would be nice, except I didn’t expect to last this long. Not in a perverse way. I lacked the creative ability: The Boy, Onyeka, could not imagine The Man, Goodness, beyond 28. The Boy reeks of over-responsibility. Intuiting a limit, he set up lofty goals – live in Paris, school in the States, do stand-up (maybe), have sex (maybe maybe) – and rushed towards them. Nailed each one, replenished in college, and now, with those also depleted into some form of completion, The Boy wavers on the ledge of a self-imposed finish line, technically satisfied but scared to tempt fate. Even if he made the leap, he’s unsure what idle youthful dreams are left to tempt with.

What am I to be?

Like, who is the person I must imagine myself as next in order to keep on living? What will the renewed deck of cards and experiences and side quests contain? If I imagined this one solid, how deep does the next go? Friend, am I correctly detailing the anxiety of aimlessness for one so practiced in laziness towards long goals? There’s an antsiness. And it helps me empathize with those that bust out a few kids, bang out a few marathons, knock out a few degrees, to fill the answer. I outlived my childish wish to be 100-years old very early. I outlived the markers I’d envisioned of success very suddenly. Though the smallness of being one life in this big blue blob, and the existentialism that accompanies it, kept on. The over-achieving impulse in my brain, the one telling me I need a new list, kept on. But I’m out of ideas of what to put on it. There are no new imaginings.

I have always been jealous of those who know and were born knowing exactly what they’re called to do. In Gr.12, my music teacher was the first adult to point out this privilege to me. She was among them, she admitted. Ever since I’ve held green eyes for anyone who possesses an innate corner piece of the puzzle; one clear edge they could use to define the rest.

The wish is to tell myself, “Lighten up. Look around. You have so much to be grateful for.” Because it’s true. And I know it, which lifts the dampen chin to peer through blurry eyes at all God has poured out upon me. All this freedom and food and promise. Still, I steal glances in between for the source of dissatisfaction. Still, I steal glances, between all this freedom and food and promise, for the source of destiny.

What am I to be?

What am I to be? Olympus is over-crowded, what am I to be? The distance to heaven is no longer distorted, pinched like the string from “A Wrinkle in Time”, what am I to be? We men fear, increasingly, that we cannot make it to where we are “meant” to be. Heaven, the head of a household, a corporation’s most honored position, heroes, historically are the positions we’ve been told we’re meant to hold. That sweet lie and its silly ultimatums, thankfully, have been debunked. Yet we can’t cope with the truth because now our humanness feels out of reach.

Since we’ve established the problem, let me pitch you how we solve it: silliness. I think our survival depends on our silliness. We’ve got to reinject silliness into our bones as if we’re pumping Play-Doh into a stone. Masculinity has been taking itself waaaaaaaay too seriously for faaaaaaaar too long, and it’s time we let our shoulders (and guards) down. We are not Prada. We are not Gucci. We’re Cartoon Network. We’re Gon & Killua. We’re Luffy at his freest. We’re a bunch of boys, who flew too close to the Sun in our hubris, craving to be weird, to be free, and free the way a nigga craves to be corny.

You might be thinking, Aren’t they silly enough? Isn’t that the problem? There’s trouble when vinegar’s mistaken for water; the same can be said when flippancy is taken for fun. The irony – as our age continues to over-steep itself in irony – is that the boys don’t feel safe. They feel the ground closing in. Crumbling their authority and potential while the (imagined) weight of the world remains on their shoulders. With shaky answers for, What am I to be?, they don’t know where to play. And in retaliation, men are misappropriating fun to not lose power: acting on every whim then claiming “whimsy”. Desperate for relevance even through the shallows of virality, we’ll do, say, disparage anything that helps us breakthrough on TikTok. “This kind of hyper-chaotic media serves as both entertainment and an ambient worldview for young men raised online. Their minds normalize prank-as-expression.”

Silly is the face that responds to a baby’s attention. Silly are the inflections used to tell children stories. Silly waves to strangers on balconies, buses, and boats. Silly is the look shared between friends when a high school math teacher does that thing they do. Silly is the sign off in the group chat that substitutes for goodnight (“Lop le Lapin snappe”). Silly are the Japanese businessmen hyping each acute and awkward spasm that barely qualifies as a dance move. Silly turns tyranny into tyranno. Only a boy could build and validate those movements, because they’re SO silly they’re borderline stupid. Each twitch and yank of their limbs proves how aggressive silly can be about fun, big or small, relishing its presence without the urge to conquer. No single body repeats another’s routine, and every body receives continued cheers exemplary of the ease, the lavish solidarity, boys will grant one another. At 2x speed it’s even better because they look primly gleeful about whatever nonsense they can offer in service to a laugh. They are playful within this fence. Careless, but doing no harm. And silly is the way they invite others in.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

If we pivot back to silly, I believe it will be easier to draw water from the stones I preached about previously. Boys, we are at our best doing silent goofy dances that help you see the joy within us and lead us to the joy to keep living. Case in point: Riz Ahmed in Fingernails, Anders Danielsen Lie in The Worst Person in The World.

Matters of Recognition

We yell that a man is “destined for greatness” when he may quietly be meant for autumnal mumblecore. My preface for Fingernails is that it’s mediocre. Filled with gems you hope would gleam nestled together, the soul-searching Jessie Buckley (“Anna”), the robotic Riz Ahmed (“Amir”), Annie Murphy for an instant, Jeremy Allen White in prime scopic moodiness, Luke Wilson making Luke Wilson-coded jokes, it barely shimmers. Glimmers, quite often from the picturesque Toronto fall it uses as a backdrop, but falters to push the love triangle at its center forward like a chipped set of French nails. Don’t get me wrong – I love a mid Rom-Com(Drahm). And this is a mid Rom-Com(Drahm) about how a test from your family’s original Windows desktop computer, reliant on your latest hangnail, tells a woman it’s alright to have two boyfriends, provided she performs an appropriate amount of hum-hawing before listening. In Christos Nikou’s defense, it was released when the word “yearning” spent half the year trending, and the year before Challengers made throuples look sexy. He does also place careful rumination around staying in a “perfect” relationship that doesn’t quite fit. But the edges are blunt. The ending dull in a way the comparisons you’ll reach for alongside the remote were easier to forgive. The results – in my opinion – inconclusive. By the credits you get the impression Nikou was daydreaming about The Lobster, his first love, while meandering through his commitment to Apple on the movie they agreed to create. (Now EYE sound like a less-than-flattering appendage…)

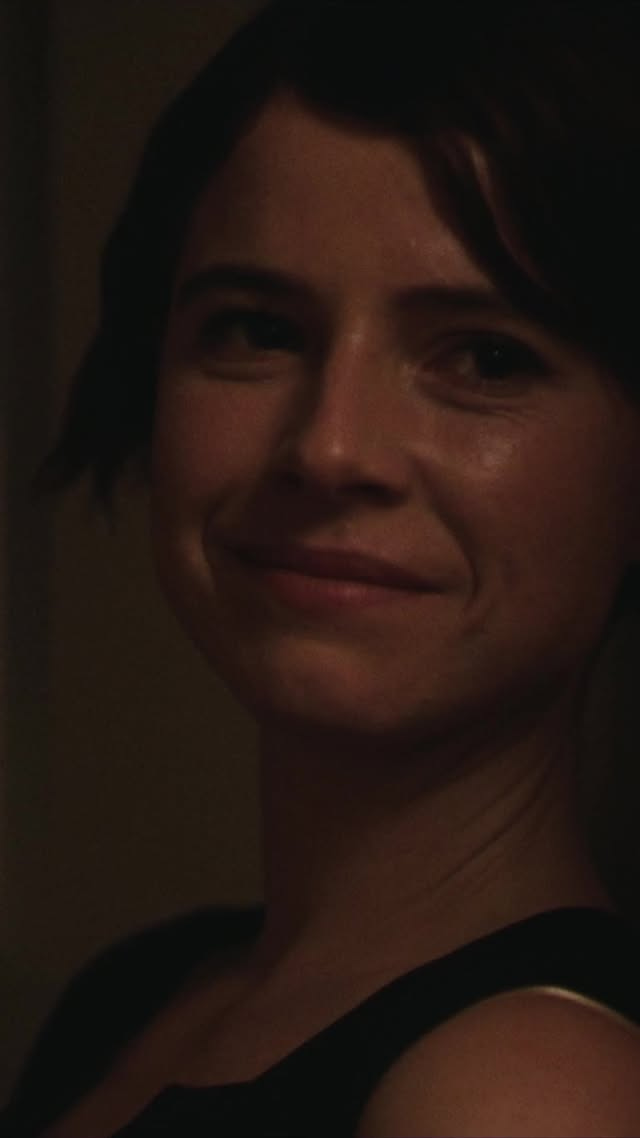

Two things he gets right. One: casting his leads based on chemistry. Buckley and Ahmed flutter around each other with a fixation that digs into your skin. They are magnetic and coquettish; pulling to and from one another in a dance of teacher-mentor, coworker-colleague, and longing desperate to be let in. The second, indelible as his fingerprint, is the way Nikou values “the act of dancing – particularly when unconcerned about public judgment – as an expression of self-determination” (LA Times). It can neither be dismissed nor discredited. He knows how to make film ‘em move and Marcell Rév (Malcom & Marie, Euphoria) knows the right way to capture it. 55 minutes in, set at the inaugural, annual office party, Jessie Buckley comes creeping down the hall with a spare slice of cake. She stops a step shy of exiting, rests lightly against the wall, eyes transfixed in a gaze she then seals with her signature smirk. Why? Because Riz Ahmed is close-eyed crushing it in the next room. Through the windowpane his torso jerks and beats, riding each wave of Frankie Vallie’s rising tenor in “The Night”. Underpinning as the baseline, the lyrics spell out each incriminating thought she’s had about her work crush, “And he always keeps you dreaming…”, punctures her science-clad defense when he hits the high hat. Nikou takes the stilted serious Amir, injects one minute of silly, free, self-assured dancing, and breaks the safety net over Anna’s heart. Any attempt to describe it returns me to Heather Havrilesky: “dance at every party like you alone know the moral to this story, it’s not too late to open all the windows, it’s cool outside today, these gods are playing the long game, patient seduction in each raindrop, let it all in and scream for more.” This is the whole movie to me. I’m positive HR banned dancing at corporate functions for this exact reason.

With a name like that you’d think it’d be about a boy. No, no. Our protagonist in The Worst Person in The World, Julie, a resplendent Renate Reinsve, is an antsy woman whose emptiness you vaguely find insufferable till her charm wins you over in the next cut. She brandishes the title like a deluxe conference pass scurrying between questionable decisions and curious, concerning actions. Plenty of men jockey for her throne along the way: her absentee, stand-offish dad infatuated with his new family; her Finding Eivind affair kicked off at his friend’s wedding (rude); Aksel, the older cartoonist she spends a good chunk of the chapters orbiting and who is kind of an asshole, until he’s caring. In this millennial age, we’ve trademarked the middle of Trier’s Oslo trilogy as a seminal European text on not having your shit together. Most days I’m in the Ross-Brody camp crying sham!6 But when I do hold my tongue, lingering through personal malaise a little longer, I defer to Bastién’s view in Vulture: “The coming-of-age genre is usually saved for teenagers and people in their very early 20s, despite the fact that the nature of being human is to be in a constant state of flux. It’s why I find coming-of-age films focused on the turbulent decades of true adulthood so ripe – when the buildup of breakups, breakthroughs, accomplishments, and beliefs is starting to loom large.” We were all itching with existential angst in 2020. For which, instead of condescension, Joachim Trier grants scores of compassion. Almost turns beautiful, like in “the time stands still” scene (its hints of My Fair Lady thrill me) and a wealth of others. If the hollowness of this messy white womanTM, unconcerned by the consequences to any of her actions, did not thrum my steady irritation, he would’ve had me. As you now know, he hit a sore spot.

Aksel, Aksel, Aksel… what a tough cookie. He was right about them being in different stages. He warns her straight up – at seven minutes and seventeen seconds – the night they sleep together. He knows himself now that he’s in his 40s, and wants to stop the ride, respectably get off, before they fall in love and into a vicious cycle of hurt. Whoopsie! They move in together. A few years after their break-up, his inane “Bobcat” comics are called out for their crassness during a national press-tour of their film release. The PR-training doesn’t hold, misogyny erupts from his fight-or-flight rebuttals in every which way. Whoopsie, pt.2! I’m unsure where that last one lands within the Johari Window model (probably under “blind spot”) but what’s certain is the writer gods felt it deserved a significant amount of punishment. Julie checks in to see how he’s doing and finds the sickly artist lost in the fury of an air-drum solo. The camera tightly tracks Aksel up from his imagined kick-pedal, past hands doing warm-ups on his lap, zooming out with the 16ths to crash in with the cymbals as his head bangs each beat for emphasis. “It’s just a way to stay alive, boy…”; that line from Turbonegro’s “Back to Dungaree High” feels too good to be true here. Anders Danielsen Lie’s pale scrunched gnarly face focused purely on jamming humbles Aksel down to a place where we can re-approach him. Inside the valley, we discover him at his best; Aksel the human, scared of dying, and not Aksel the Asshole, insecure over his legacy. The scene is brief, neat, and under a minute, but it’s crucial as prelude for where Trier plants his flag. To explain, I’ll defer to Bastién again, “A conversation framed by swaying trees, their shared history bearing down on the pair, brought up a host of emotions I still have no receptacle for — emotions tethered to a fear of mortality, a fear that I’m not doing enough, a fear that what it is I do day in and day out isn’t quite being alive.”

I want to see all my homies alive.

Walk them back to their humanity, sit them down in silliness. On bended knees I’ll plead them off their high horse. What is it you believe the moon rises and the sun sets by? Why did you invest in a fool’s gold chariot to drag orbs across the sky?7 Ogilvy and Sinek might be ashamed of such an approach. But the promise is simple: you won’t be as alone. There are more mortals than men – that’s why the gods choose to strike us down.

If you have to be anything, be chill. Be a chill silly guy. Give yourself the gift of rest and be grateful for it. That you even can. And that you have the time, the personality, the wonder, and there’s more left inside. Boys are at their best doing goofy, silent, imperfect dances that help you see the joy within us and lead us to the joy to keep living. The rest is just marketing. A fable strummed up by talented execs in semi-tall towers. I’d synch “Fable” by Gigi Perez if you ever need a gracious reminder, and I’ll play “Conversations” by Your Grandparents in case you ever want to talk about any overwhelming feelings.

P.S. In Igbo “I love you” means and translates to “I see you”.

“Raise your sights! Blaze new trails!! Compete with the immortals!!!” – David Ogilvy

I had nowhere else to include this video, and I really liked this snippet of their convo - and both of their movies this year! - so here. Drink some water!

Reign? Rein? Purple Rain?

“The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think.” - Virginia Woolf

Deborah Ross’ review means everything to me… I read it and wish I wrote it.

Apollo Driving the Chariot of the Sun - Leilo Orsi

a hurum gi n’anya 🌟